Robinet Testard

Frans boekverluchter. Zijn lange loopbaan begon in de vroege jaren 1470 in Poitiers met de verluchting van een Grandes Chroniques de France (Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr 2609). Net na 1480 treedt hij in dienst van Charles d’Orléans in Cognac. Zijn loopbaan eindigt rond 1531. Hij werd vroeger genoemd de Meester van Charles d’Angouleme, dit naar een aantal handschriften dat hij verluchtte voor Charles de Valois, graaf van Angouleme. Ook Louise de Savoie, echtgenote van Charles d’Angouleme, behoorde tot zijn opdrachtgevers.

De artiest werd uiteindelijk geïdentificeerd via rekeningen uit het huishouden van de graaf. In 1484 werd Robinet Testard gepromoveerd tot Valet de Chambre van de graaf. Betalingen voor door hem verluchtte manuscripten worden gedaan door achtereenvolgens de graaf, zijn weduwe, Louise van Savoie, en hun zoon, François I, koning van Frankrijk, die hem een pensioen toekent in 1523. Hij wordt voor het laatst genoemd in 1531 bij de vereffening van diens nalatenschap: “le vieil Robinet, paintre, reçoit alors 80 livres (bron: Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms. fr. 3054, f. 28v).

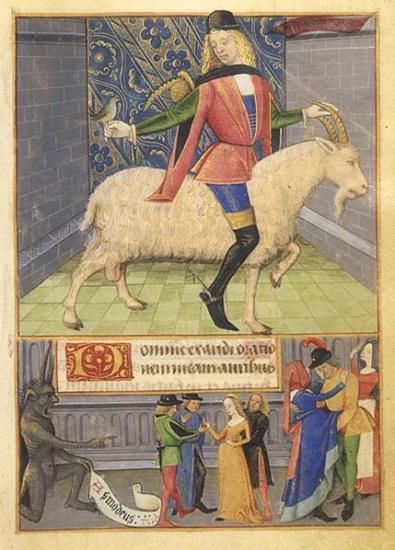

New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, ms 1001, f. 98r: Lust

De artiest onderscheidt zich door zijn originaliteit en humor. In een in ca 1475 vervaardigd getijdenboek (thans New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, ms M 1001) wordt in een voor getijdenboeken ongewone serie miniaturen een verband gelegd tussen de Zeven Boetepsalmen en de Zeven Doodzonden. Iedere psalm wordt geïllustreerd met een personificatie van de zonde waartegen de psalm is gericht. Het onderste gedeelte van de afbeelding bevat voorts een nadere aanduiding van de personificatie. Zo zien we op fol. 98r een afbeelding van “Lust” die suggestief de hoorn van een geit betast, terwijl hij kijkt naar waarschijnlijk een nachtegaal, welke vogel de verboden begeerte zou aanmoedigen. In de bas-de-page zien we de demoon Asmodeus die mannen en vrouwen aanmoedigt de zonden van het vlees te begaan.

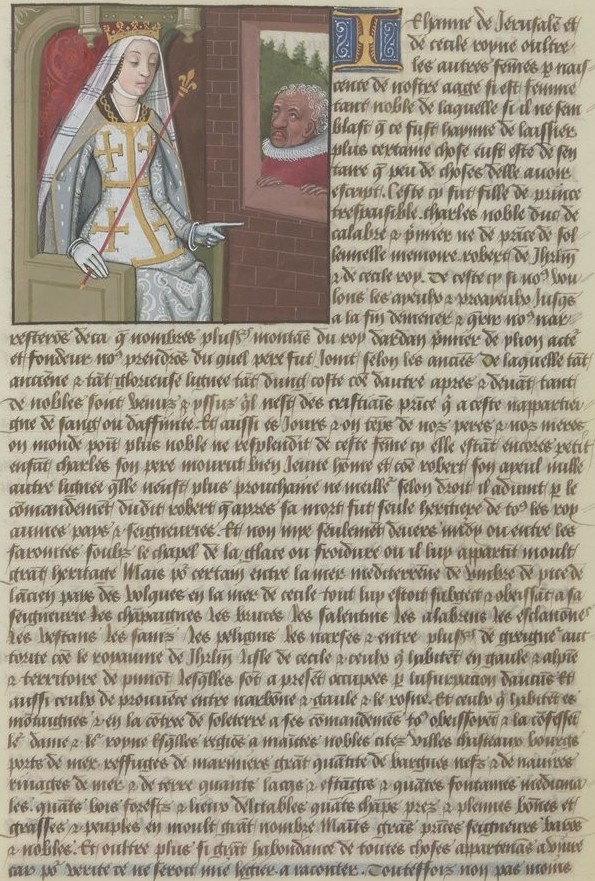

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 2609, f. 230r (detail)

Tot de hoofdwerken van Testard behoort getijdenboek dat hij samen met Jean Bourdichon verluchtte voor de reeds genoemde Charles d’Angouleme en dat thans bewaard wordt in de Nationale bibliotheek in Parijs (Ms. lat 1173). In dit handschrift gebruikt Testard voorbeelden uit de Nederlandse grafiek, waarbij hij zelfs kopergravures van Israel van Meckenem inkleeft en inkleurt. Ook bevat zijn werk veel ontleningen aan de paneelschilderkunst van de Vlaamse primitieven. Dit laatste element uit de kunst van Testard treffen we ook aan in een album met een aantal losse bladen uit een getijdenboek (Sotheby’s, 6 juli 2000, lot 42), zo bijvoorbeeld folio 18 met de Bewening.

Een aantal afbeeldingen uit het Getijdenboek van Charles d’Angouleme nader beschouwd.

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 7v: Christ Pantocrator

Christ Pantocrator on folio 7v in the Gospel lessons, i.e. at the very beginning of the book of hours, is in fact an engraving by Israhel van Meckenem altered by Robinet Testard. The original print depicted several of the main characters in the New Testament and the Church inside a circle, with John the Baptist in the centre, garbed in a camel skin and a large blanket, sitting in the desert pondering over an open book, and the Lamb of God lying on his right. Inside the medallions around him, separated by ornamental foliate motifs inhabited by birds, are the four symbols of the evangelists arranged in a Latin cross: John’s eagle at the top, Mark’s winged lion on the left, Matthew’s angel at the bottom, and Luke’s bull on the right. Depicted in other medallions are the four doctors of the Church: Jerome and the lion at the top on the left; Gregory at the top on the right, recognisable by his papal tiara; Augustine writing at the bottom on the right; and Ambrose at the bottom on the left.

Testard retains the circular layout used in the print but replaces John the Baptist by Christ in majesty giving a blessing and surrounded by angels. He follows the figures in the print almost exactly apart from changes to their faces and some slightly different postures. He fills the page by painting foliate motifs in the spaces around the circle and adding four prophets, one of whom – Jeremiah at the top on the left – can be recognised by his phylactery bearing a phrase from the book dedicated to him, “Ecce dies veniunt” (Jer. 23: 5-6).

Testard thereby provides a liturgical introduction for the book of hours in the form of a synthetic image of the Church which depicts the main pillars of the Christian faith in the Old Testament (prophets), the founding theologians (the four doctors) and the evangelists. Israhel van Meckenem’s print, a copy of an earlier print by Master E.S. dated 1466, was probably meant to be a pattern for a round object made of gold or silver, in all likelihood a paten. Testard’s direct use of the print here created a compact, effective diagram to which he made appropriate additions. The resulting image is a welcome change from the individual portraits of one or more evangelists usually found at this point.

(Source: Séverine Lepape, Curator, Musée du Louvre).

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 20v: country dance

Terce in the Hours of the Virgin, the Cross and the Holy Ghost is preceded by a scene of a country dance: a rather surprising portrayal of country life where one would expect to find a Holy Scriptures scene. This dance, totally unrelated to this section of the book of hours, seems at first glance to be a continuation of the calendar featuring other everyday scenes. In a landscape with no real perspective typical of Robinet Testard’s art, and outside a town in the background, a dance takes place around a tree forming the centre of the composition. The figures have clean-cut outlines and are arranged as if in a stage setting. Several sheep, rams and dogs heighten the picturesque nature of the scene.

The reason for this odd image might have been a desire to insert an engraving that the patron would particularly like, as occurs elsewhere in the manuscript. This is, however, not the case because this image is an illumination painted directly on the parchment folio. Moreover, no engraved source has been identified. The country dance in the Hours of Charles of Angoulême is, in fact, a mixture of religious and picturesque elements. The kneeling angel painted in the sky is surrounded by a long phylactery bearing the words Gloria in excelsis Deo…”. One of the three shepherds not dancing – two in the background and one on the edge of the scene – points at the heavenly angel. The group is obviously reminiscent of the Annunciation to the shepherds despite usually being set at night.

Terce in the Hours of the Virgin, the Cross and the Holy Ghost is preceded by a scene of a country dance: a rather surprising portrayal of country life where one would expect to find a Holy Scriptures scene. This dance, totally unrelated to this section of the book of hours, seems at first glance to be a continuation of the calendar featuring other everyday scenes. In a landscape with no real perspective typical of Robinet Testard’s art, and outside a town in the background, a dance takes place around a tree forming the centre of the composition. The figures have clean-cut outlines and are arranged as if in a stage setting. Several sheep, rams and dogs heighten the picturesque nature of the scene. The reason for this odd image might have been a desire to insert an engraving that the patron would particularly like, as occurs elsewhere in the manuscript. This is, however, not the case because this image is an illumination painted directly on the parchment folio. Moreover, no engraved source has been identified. The country dance in the Hours of Charles of Angoulême is, in fact, a mixture of religious and picturesque elements. The kneeling angel painted in the sky is surrounded by a long phylactery bearing the words Gloria in excelsis Deo…”. One of the three shepherds not dancing – two in the background and one on the edge of the scene – points at the heavenly angel. The group is obviously reminiscent of the Annunciation to the shepherds despite usually being set at night.

(Source: Maxcence Hermant, Curator, Bibliothèque nationale de France).

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 41r: dood van de centaur

Folio 41r contains undoubtedly the most peculiar illumination in the entire manuscript. A centaur with a wild woman on his back is attacked and about to be slain by two half-naked men wielding axes. But the arrows that have hit the centaur and his rider were fired by Death himself, a bony corpse above them aiming deadly arrows. Depicted on the left in the background is a lion wandering along the edge of a forest, and on the right, a castle on a promontory. Death is the link between this illumination and the place where it appears, i.e. in the Office of the Dead, but this does not explain the rest of the composition, a strange combination of an Italian iconographic subject (the battle of the centaur) and a northern subject (the wild woman).

Robinet Testard did in fact base his illumination on an engraving attributed to IAM, an artist who probably came from Zwolle in the Netherlands or worked there in 1470-1495. The engraving by IAM shows only the group in the foreground – the centaur, with no rider, and the two men – and was probably the first picture of a centaur in fifteenth-century, northern engravings.

The theme of a centaur ravishing a young woman is to be found in many series of images about Hercules and the tale of his wife Deianira, a theme rediscovered by Renaissance artists whilst copying and studying the bas reliefs of antiquity. But Robinet Testard apparently sought to emphasise the northern rather than the Italian flavour of the composition by adding this wild woman so popular in fifteenth-century German art and engravings from the outset (particularly in the playing cards engraved using the burin technique in 1430-1440 by the Master of the Playing Cards, an artist active in the Upper Rhine area).

The figure of Death added to this scene is depicted as in illuminations from the 14th century onwards, e.g. the illustration of the famous passage of the three dead and the three living in the Psalter of Bonne of Luxembourg illuminated by Jean le Noir before 1349.The image in this instance is, therefore, a product of these different sources. Its meaning, however, remains obscure. Is it a moralising allegory of the triumph of death over beasts; or merely an artistic whim intended to demonstrate how knowledgeable and interested the manuscript illuminator and, perhaps, Charles of Angoulême were in the iconographic innovations of Germany and Italy, the two most dynamic hubs of production in the late Middle Ages (Source: Séverine Lepape, Curator, Musée du Louvre).

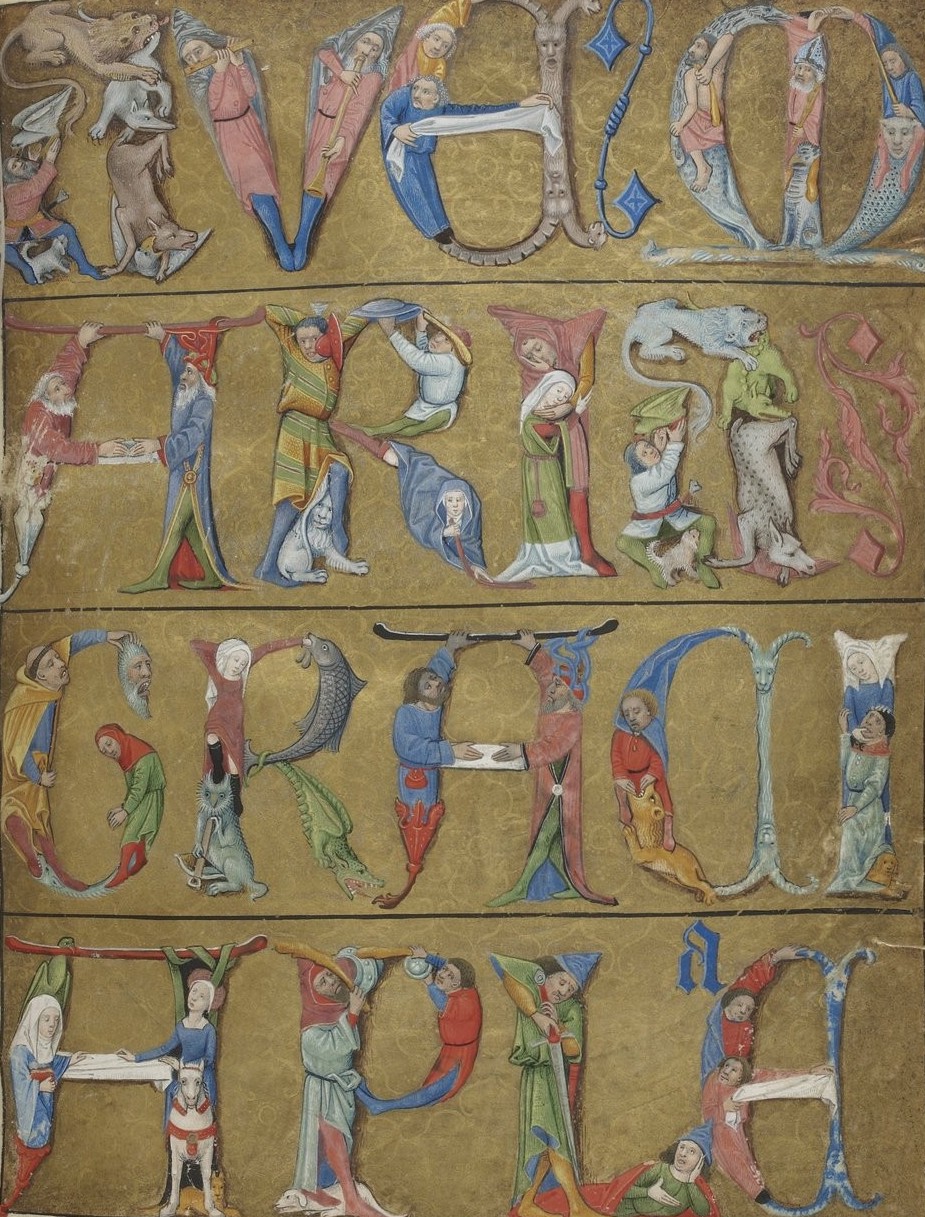

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 52r: alfabet met Ave Maria

The opening words of Ave Maria at folio 52r are spelt out in anthropomorphic initials covering an entire page upon a golden ground. The different figures and animals are shown interwoven or attacking each other or playing music. The result is very striking; the letters contrast so sharply with the golden ground that they seem to stand out from the folio. The way the letters are put together is a sort of visual or mental exercise in which fighting animals and whimsical elements do not seem to detract from the holy prayer to the mother of Christ. Large initials were often used as a framework for imagery in medieval illuminations, particularly historiated initials. But the initials in this instance do not contain images: they are actually formed by different figures. The earliest examples of such initials are those in a manuscript copied at Cîteaux abbey in the early 12th century, Moralia in Job, which consist of a variety of figures including jugglers, and monks cutting wood or harvesting.

In the late 1460s, Master E.S. created a complete alphabet in this style – far bolder and colourful than the distant models of the Romanesque era. He was inspired considerably by the Taccuino di disegni, the illuminated pattern book by Giovannino de’ Grassi dating from the late 14th century. The prints by Master E.S. were a standard that Robinet Testard must necessarily have seen, as revealed by the letter A at the beginning of Ave Maria which was an accurate copy of the same letter by Master E.S. However, Testard apparently had access to another woodblock alphabet dated 1464 from Flanders or the Netherlands which he used as a model. All the other letters are in fact copied directly from that alphabet, including the first letter A in the word Maria, which the first A in the word Gracia is an almost identical copy of.

Two of these alphabet series are to be found in London (British Museum, B,10.1-23 (incomplete) and 1947,0724.1-19 (incomplete). There is also a woodblock copy in Basle, and the Master of the Banderoles, an engraver active in Flanders between 1450 and 1475, created a dry-point version too. It is difficult to be sure which version Robinet Testard had in front of him but a comparison of some letters in the 1464 alphabet with those in engraved copies by the Master of the Banderoles, suggests that the Parisian illuminations bear a greater resemblance to the copies by the Flemish engraver. This should come as no surprise because, as we have seen, Testard often used German and Netherlandish engravings as a source of inspiration for his motifs.

(Source: Séverine Lepape, Curator, Musée du Louvre).

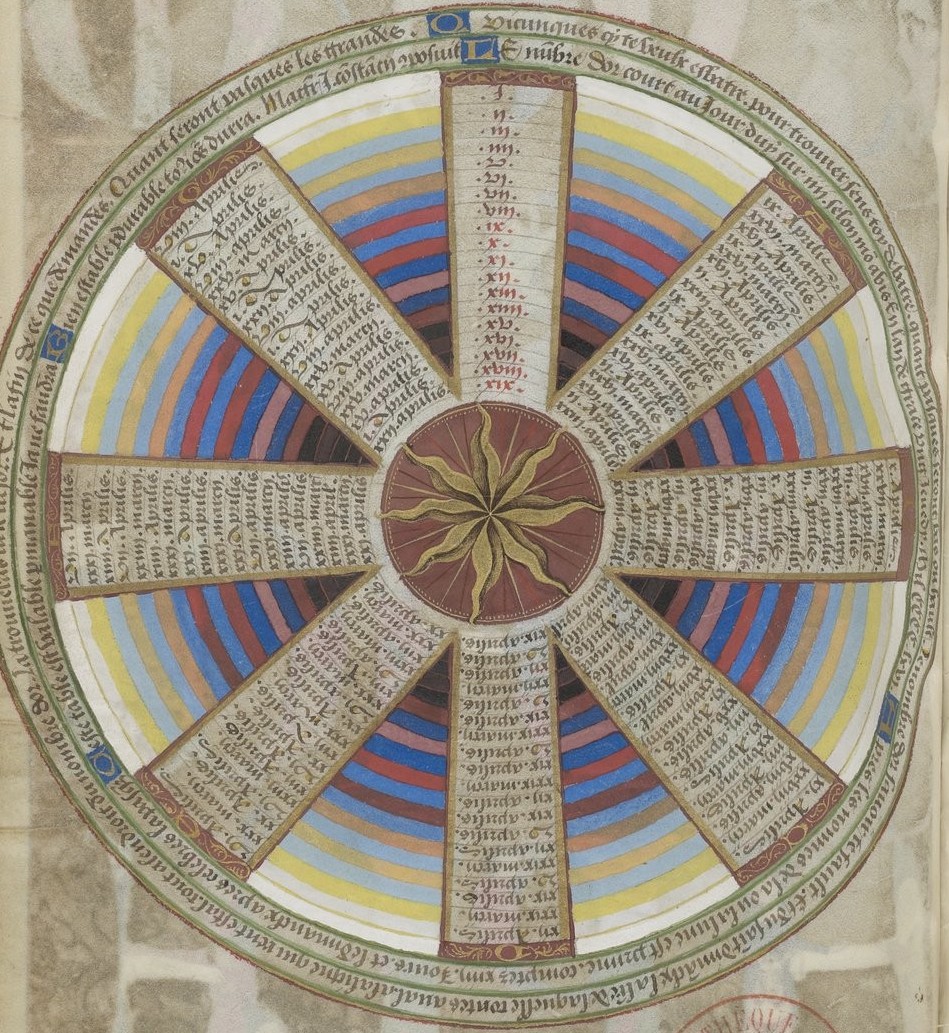

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 52v: diagram

On the back of the remarkable Ave Maria in large initials is an equally unusual diagram which must originally have been even more striking than it is now. At the outset, the vivid colours of the concentric circles behind the diagram must have stood out more clearly against the cream-coloured parchment. Indeed, one of the components used to make the golden ground of the Ave Maria, probably silver, has gone rusty and seeped deep into the parchment. The diagram consists of spokes extending from a circle in the centre decorated with a sun to two outer circles bearing instructions about how to use the diagram. The main spoke, at the top, contains a sequence of Roman numerals in red ink from I to XIX: the golden number used to calculate the dates of the new moon and, therefore, Easter. Written on the other seven spokes are the possible dates of Easter, calculated by using the golden number of each year.

(Source:

Maxcence

Hermant, Curator, Bibliothèque

nationale de France).

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 53v: St. George slaying the dragon

The book of hours ends with suffrages to two saints: St Anthony and St George. St Anthony was very popular in the Middle Ages. He was venerated particularly for resisting the Devil’s temptations and also regarded as a patron against different illnesses. St Georges, depicted here in a print by Israhel van Meckenem which Robinet Testard coloured slightly, refers to a higher-ranking world. St George was the patron saint of medieval chivalry in Europe and of all military orders (Teutonic Order, Order of the Garter, etc).

The legend about this saint, set down in writing by Jacobus de Voragine in the 13th century, tells how he saved the king of Silene’s daughter from being fed to a dragon wreaking havoc in the region. The saint braving the monster represents the victory of the Christian faith over the Devil and Evil. The importance given to this saint in this manuscript is not surprising: being a prince of royal blood, Charles of Angoulême was obliged to show particular deference to knightly symbols. The choice of this dragon-slaying saint rather than St Michael, the patron saint of the crown of France from Louis XI onwards, was probably the result of a desire to disassociate Charles from the king of France. St George resembles St Michael in many respects: they both slew evil and were regarded as military saints.

In addition, in 1469 Louis XI created a new order of knights in honour of St Michael. It is not known whether Charles of Angoulême belonged to that order but his interest in St George suggests he did not. Finally, the choice of St George was also a reference to Louise, Charles of Angoulême’s wife. She belonged to the dynasty of the dukes and princes of Savoy which held this saint in very high esteem, alongside St Maurice, another military saint. Robinet Testard made virtually no changes to the illumination apart from the princess’s headwear, replacing her conical hat and veil with the turban more in vogue in the 1480s.

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms lat. 1173, f. 106v: Bewening

In the foreground, the Virgin holds Christ’s body with the help of Joseph of Arimathea. Mary Magdalene stands near her, wringing her hands in grief. Behind them, forming a frieze, St John and the holy women weep. On the right, Nicodemus prepares the tomb for Christ’s body. In the background, Joseph, Nicodemus and Our Lady pick up Christ’s body taken down from the cross.

The influence of Roger van der Weyden and his epigones can be seen here in the portrayal of the group in mourning. Likewise, St John wiping his eyes is directly inspired by Jan van Eyck’s panel of the Crucifixion now housed in Berlin. Because of the age of the works used as models, it is not inconceivable that Meckenem was aware of these two paintings thanks to an engraving by Master E.S. to whom they are attributed and who died in the late 1460s. Although Meckenem portrays the figures in great distress, he does not show them weeping, whereas Testard painted tears running down the cheeks of Our Lady, Mary Magdalene, St John and several holy women, which suggests that he too was familiar with the work of Roger van der Weyden, one of the first artists to portray the crystal-clear tears of the persons close to Christ so masterfully in different paintings.

(Source: Séverine Lepape, Curator, Musée du Louvre).

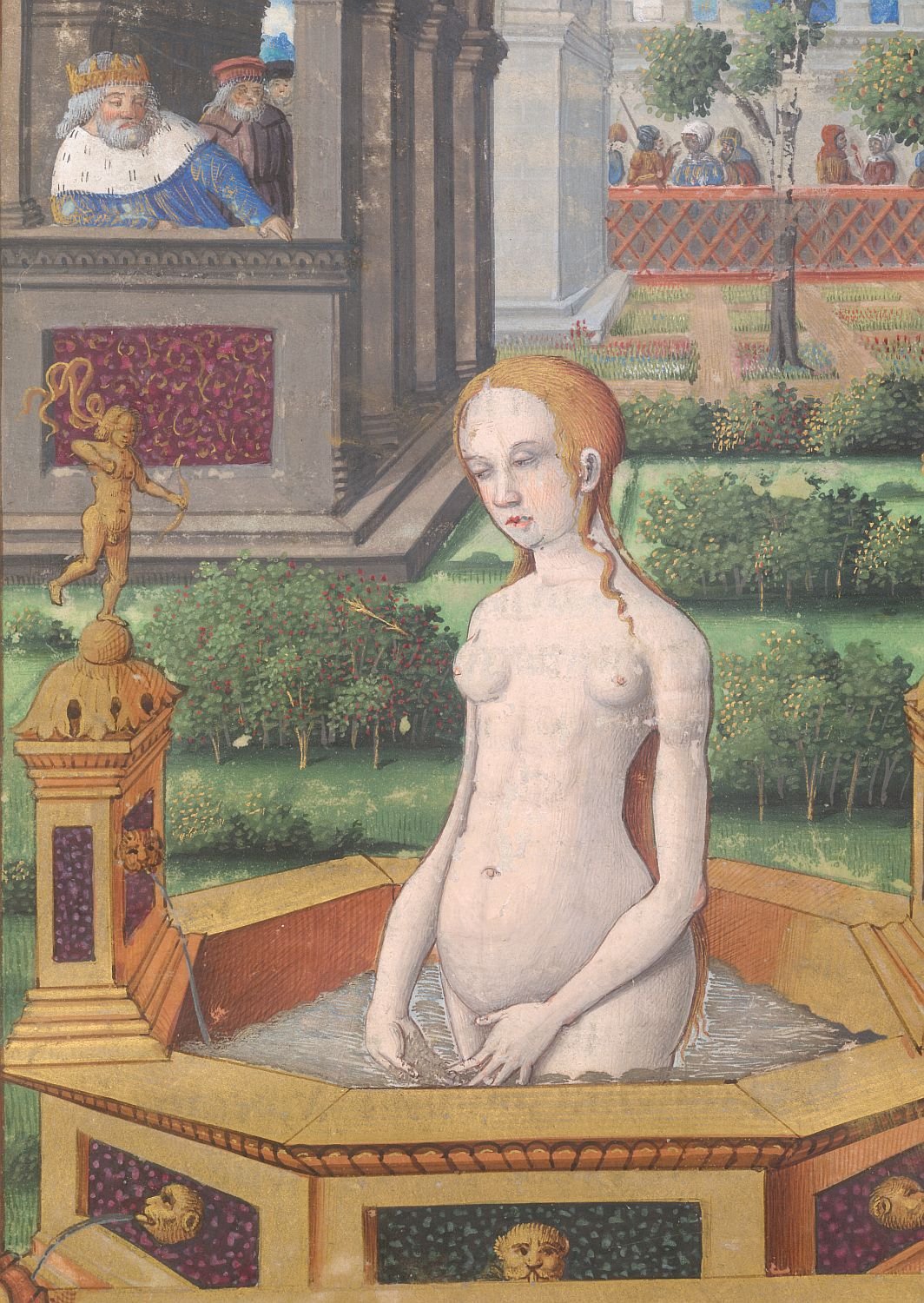

Londen, British Library, Ms Kings 7, f. 54r: Bathsheba (detail)

Catalogus

Besançon, bibliothèque municipale

Ms 150 getijdenboek, Cognac, ca 1500

Literatuur:

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, p. 403

- Sotheby’s 6 juli 2000, in lot 42

Brussel, Koninklijke Bibliotheek

Ms 15077 getijdenboek van Rochefoucauld

literatuur:

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, p. 403

- Sotheby’s 6 juli 2000, in lot 42

Londen, British Library

Ms Kings 7 getijdenboek, Cognac, ca 1500 deels verlucht door werkplaats van Robinet Testard: ff. 7, 19, 26, 27, 28, 31, 37, 40, 45, 54, 66v, 70; en deels door werkplaats van Jean Pichore: ff. 34, 100 en alle kleine miniaturen

literatuur:

- Warner & Gilson 1921, III, p. 3-4

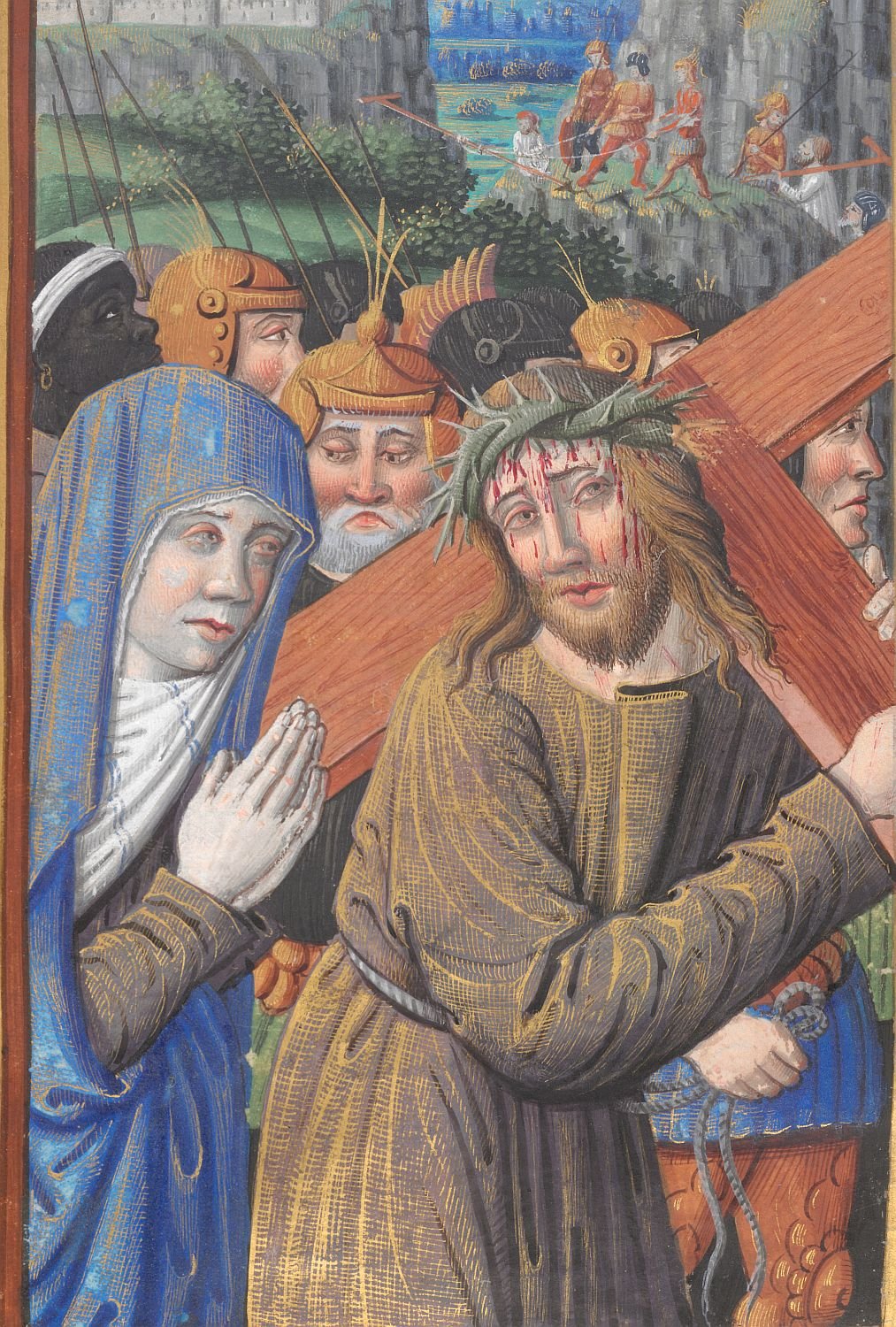

Londen, British Library, Ms Kings 7, f. 26r: Kruisdraging (detail)

Londen, Sotheby’s

Catalogus 6 juli 2000, lot 42 album met 19 miniaturen uit een getijdenboek, Poitiers, ca 1470-85

literatuur:

- König 1989 (1), nr. 68

- Sotheby’s 6 juli 2000, lot 42)

New York, Pierpont Morgan Library

Ms m 1001 getijdenboek, Poitiers, ca 1475

literatuur:

- Plummer 1982, nr. 62

- Wieck 1997, nrs. 75, 79

Oxford, Bodleian Library

Ms douce 195 Guillaume de Lorris & Jean de Meung, Le Roman de la Rose, Frankrijk, eind 15e eeuw, miniaturen in de stijl van Robinet Testard

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Douce 195, f. 76v, 45r, 122v

literatuur:

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale

Ms fr 143 Les Echecs amoureux, ca 1496-98

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 143, f. 28r (detail)

literatuur:

- Durrieu & Vasselot 1894

- Parijs 1904, nr. 191

- Parijs 1907, nr. 80

- Blum & Lauer 1930, p. 45, 88-89, pl. 68

- D’Ancona & Aeschlimann 1949, p. 203

- Parijs 1955, nr. 344

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

- Parijs 1990, nr. 43

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, nr. 232

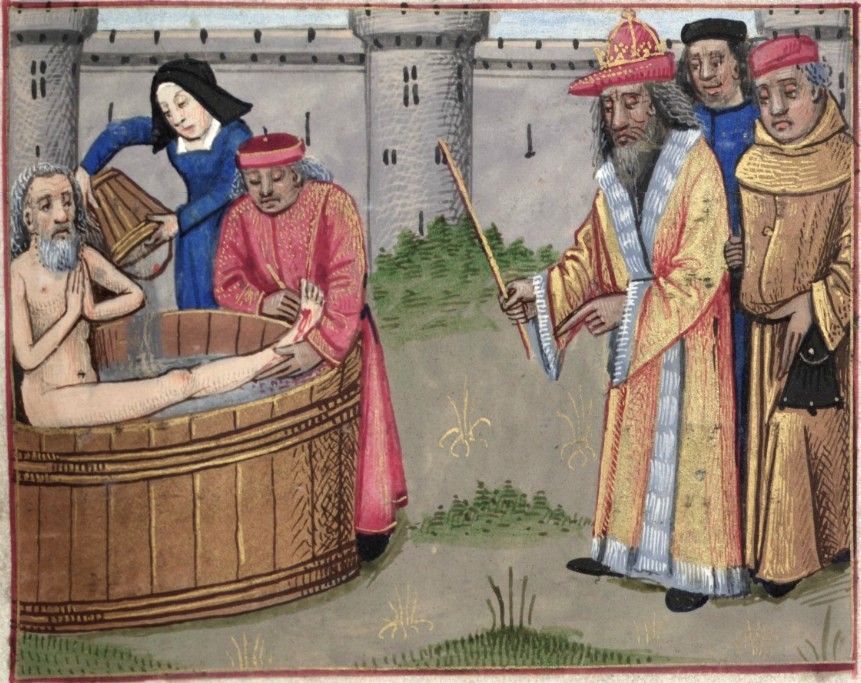

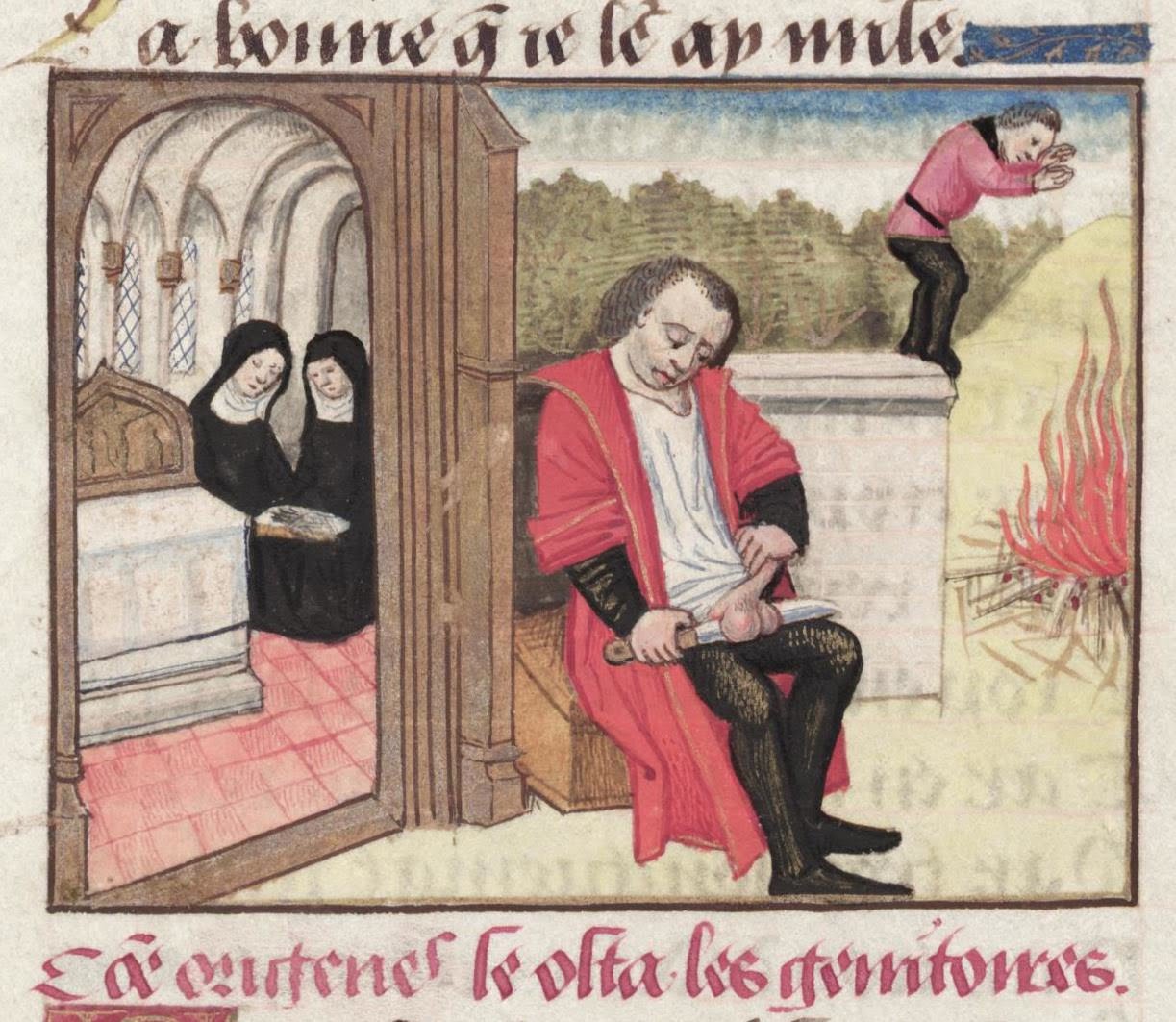

Ms fr 231 Boccaccio, De Casibus (Franse vertaling door Laurent de Premierfait), Cognac, ca 1500

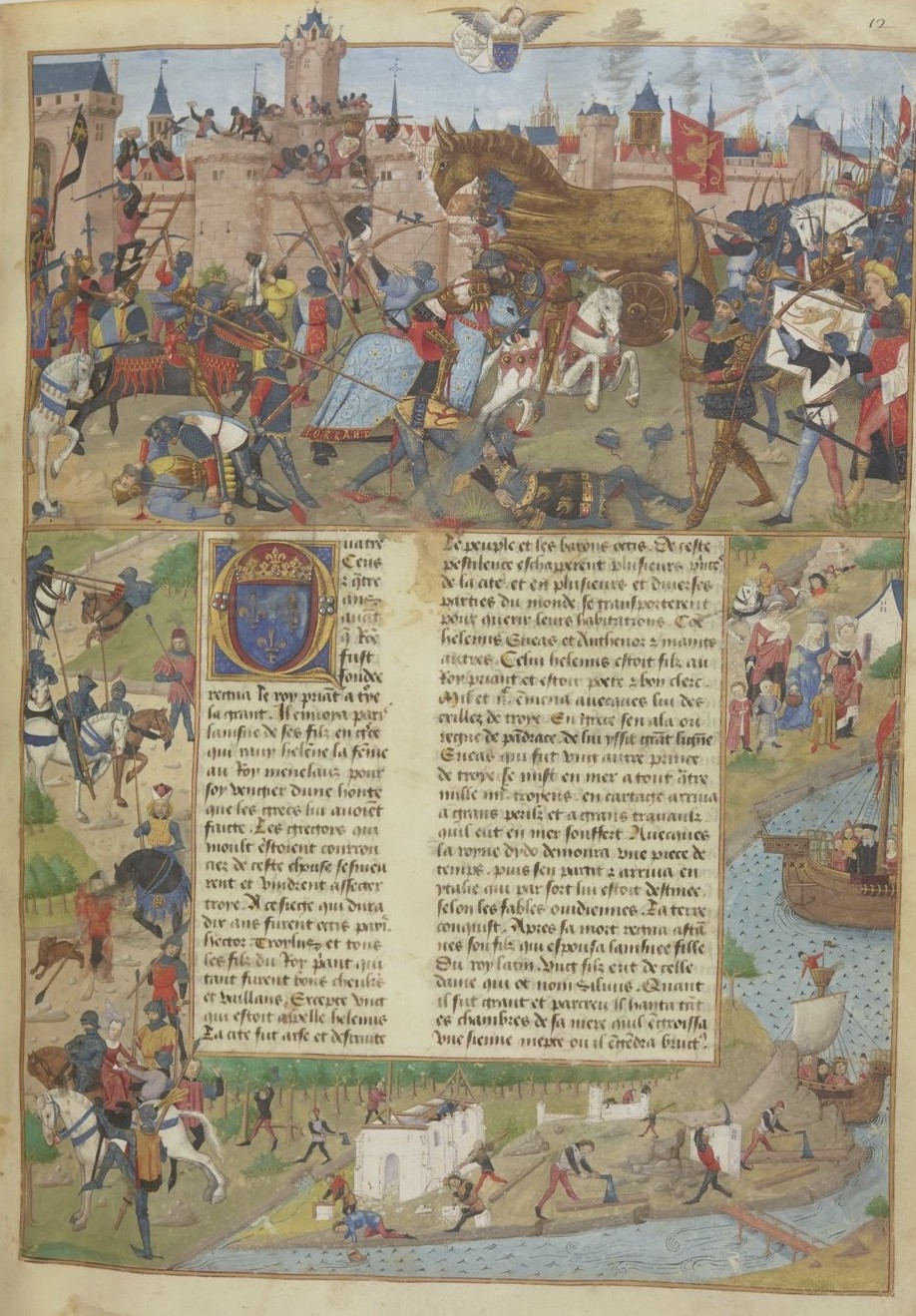

Ms fr 252 Raoul Lefèvre, Histoire de Troyes, Cognac, ca 1500

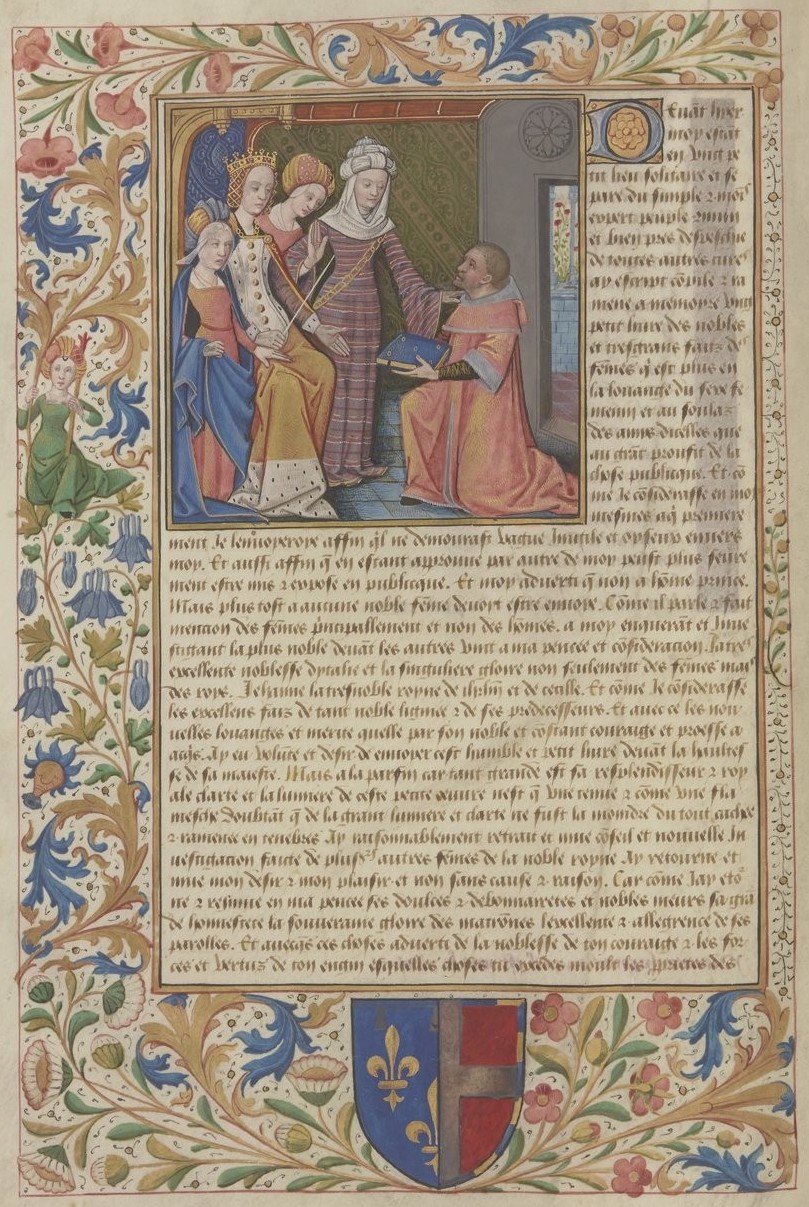

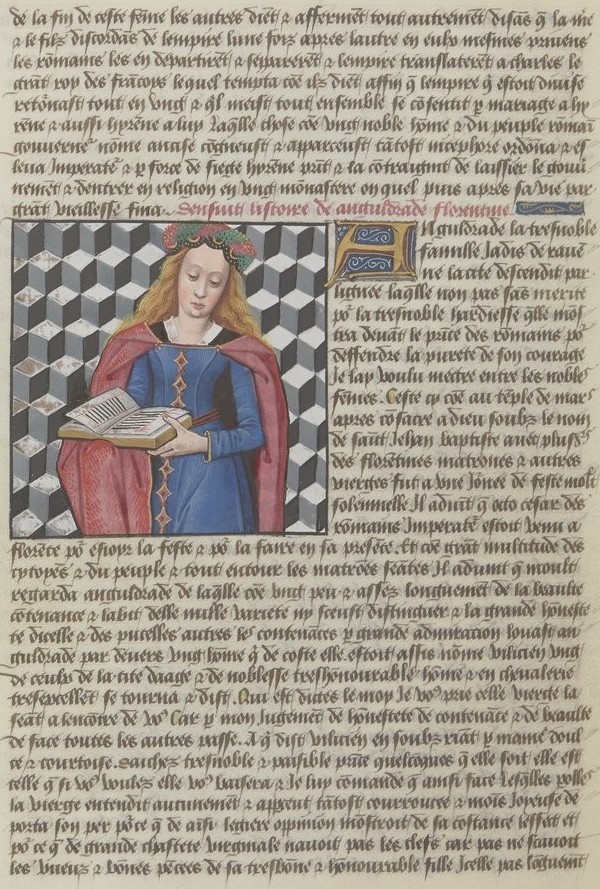

Ms fr 599 Boccaccio, Des claires et nobles femmes, eind 15e eeuw

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 599, f. 2v, 89v, 93v

literatuur:

- Parijs 1955, nr. 345

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

Ms fr 875 Les Epitres d’Ovide, Cognac, tussen 1496-98

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 875, f. 58r (detail)

literatuur:

- Durrieu & Vasselot 1894

- Blum & Lauer 1930, p. 88, pl. 67

- D’Ancona & Aeschlimann 1949, p. 203

- Parijs 1955, nr. 346

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, nr. 231

- Parijs 1995, nr. 56

Ms fr 929 Jean Gerson, Le Livre tres salutaire de la Ymitacion Jhesu Crist, Cognac, ca 1500

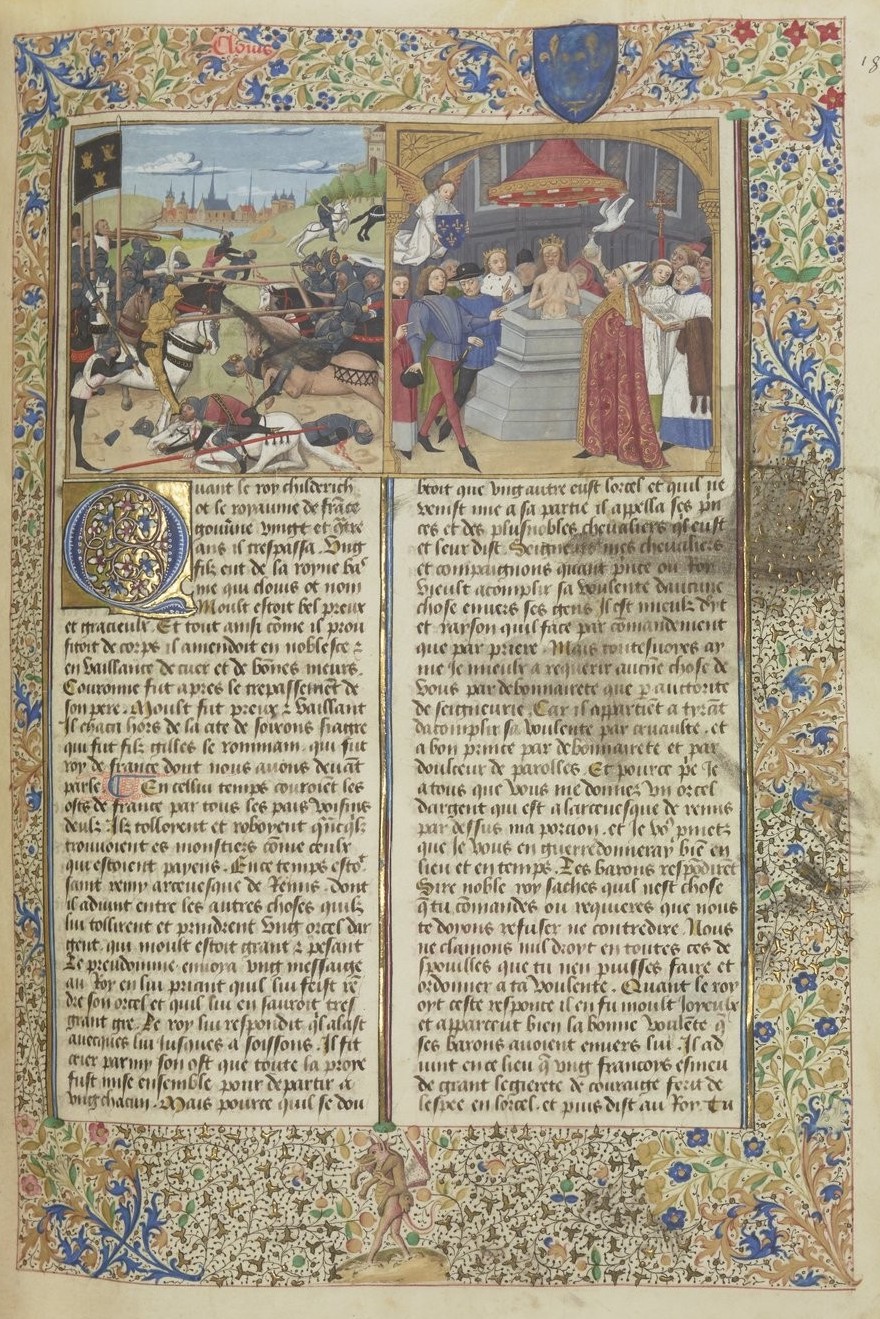

Ms fr 2609 Grandes Chronique de France, Poitiers, ca 1471-1480 verluchting door Robinet Testard en Meester van Marguerite de Rohan: laatste miniatuur

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 2609, f. 12r, 18r

literatuur:

- Hermant 2015, p. 64

Ms fr 2825 Histoire de la guerre sainte de Guilaume de Tyr, ca 1480-1490 miniatuur op f. 1r toegevoegd aan 13e eeuw handschrift door Robinet Testard toen handschrift behoorde aan Charles d’Angoulême

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 929, f. 7r: Le Christ portant sa croix devant Charles d’Angoulême

Ms fr 12247 François Demoulins, Traité des vertus, Lyon, na 1509?, verluchting door Robinet Testard: 2 miniaturen geplakt op binnenzijde boekbanden, overige verluchting door Guillaume Le Roy

literatuur:

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 12247, NP

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, nr. 204

- Burin 2001, nr. 123

Ms fr 22971 Merveilles du monde ou les Secrets de l’Histoire naturelle, Cognac, ca 1480-1485

literatuur:

- Parijs 1955, nr. 342

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, nr. 229

Ms lat 873 Les Espitres d’Ovide, Cognac, ca 1500 verluchting door Robinet Testard: f. 21r; Meester van Yvon du Fou: overige verluchting

literatuur:

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, p. 403

Ms lat 1173 Heures de Charles d’Angouleme, Cognac, ca 1482-1485 verluchting door Robinet Testard en Jean Bourdichon: f. 9v geboorte, 22v aanbidding door de wijzen

literatuur:

- Durrieu & Vasselot 1894

- Blum1911

- Mély 1913, p. 197

- Leroquais 1927, I, p. 104-8, pl. XCII-XCV

- Parijs 1937 (2), nr. 191

- Tours 1952, nr. 35

- Parijs 1955, nr. 343

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

- König 1989 (1), p. 468

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, nr. 229

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 875, f. 36: Dido schrijft aan Aeneas

San Marino, Huntington Library

Ms HM 60 Les Epitres d’Ovide, Cognac, rond 1500

literatuur:

- Parijs 1995, p. 175

Sint Petersburg, Koninklijke Bibliotheek

Ms fr F.v.vi, 1 Dioscurides

literatuur:

- Plummer 1982, p. 47

Londen, British Library, Ms Kings 7, f. 7r: Annunciatie (detail)

Literatuur

- Delisle 1878-1881, I, p. 184

- Bradley 1887-1889, III, p. 293

- Durrieu & Vasselot 1894

- Parijs 1904, nr. 191

- Parijs 1907, nr. 80

- Blum 1911

- Mély 1913, p. 197

- Warner & Gilson 1921, III, p. 3-4

- Leroquais 1927, I, p. 104-8, pl. XCII-XCV

- Blum & Lauer 1930, p. 45, 47; p. 88, pl. 67; p. 45, 88-89, pl. 68

- Parijs 1937 (2), nr. 191

- Tours 1952, nr. 35

- Parijs 1955, nrs. 342-346

- Plummer 1982, nr. 62, p. 46, 47

- König 1989 (1), nr. 68, p. 463-471

- Parijs 1990, nr. 43

- Avril & Reynaud 1993, p. 402-6, nrs. 204, 228, 229, 231, 232

- Parijs 1995, nr. 56, p. 175

- Wieck 1997, nrs. 75, 79

- Sotheby’s 6 juli 2000, lot 42

- Burin 2001, nr. 123

- http://gallica.bnf.fr

- Hermant 2015, p. 64

Parijs, Bibliothèque Nationale, Ms fr 143, f. 198v (detail)

- Bradley 1887-1889 –

- Thieme-Becker 1907-1950

- D’Ancona & Aeschlimann 1949, p. 203